Human factors engineers conduct usability testing sessions to inform medical device manufacturers on whether a device is safe and effective before commercialization. Such testing sessions often include both healthcare professionals and patients. To ensure that the results gathered in a usability study will reflect actual use case scenarios, usability studies are conducted in simulated-use environments that closely represent the real-world use environments of the device being investigated, as specified in the FDA Guidance.

By immersing participants in a realistic, simulated-use environment, we gain valuable insights on how to mitigate use-related issues through improvement to the device design. However, we must pay close attention to participants who might become distressed during a usability study due to past trauma that may resurface. As human factors engineers, we can learn best practices for identifying and managing participant distress that might be triggered by simulated use environments.

How is trauma learned?

We know from Watson’s classic Little Albert Study (1920) that fear, or trauma, can be learned through associations between fear stimuli and previously neutral stimuli. People may experience a traumatic event while simultaneously being exposed to a variety of auditory, visual, olfactory, and tactile cues that are present in an environment. These seemingly neutral background cues can become associated with a traumatic event, in that a person may recall the traumatic event when later sensing the background cues on their own. For example, if a person previously received painful treatments (unconditioned stimuli) while being exposed to the sound of a heart monitoring alarm (neutral stimulus), it’s possible that they might recall the negative experience when hearing auditory cues from a heart monitoring alarm at a later time (e.g., during a usability study).

Although we cannot avoid conducting usability studies in realistic, simulated-use environments, we can be prepared to identify which stimuli in the environment may cause participant distress and how to manage it to both protect the participant and maintain the integrity of the data being collected.

Who is vulnerable?

Everyone is susceptible to experiencing medical trauma, but there are some populations who are more likely to experience it than others.

Patients with chronic disease

Patients with chronic disease (i.e., a disease that lasts longer than three months) may experience trauma during a variety of events, including their initial diagnosis, long hospital stays, or treatment plans. Nearly 40 million Americans are limited to their usual activities due to one or more chronic health conditions, and almost a third of this population is now living with multiple, chronic conditions.

Medical device usability studies are often conducted with patients living with chronic disease because they frequently interact with medical devices both in the presence of healthcare professionals as well as independently. These participants may be exposed to sensory stimuli in the simulated-use environment that were also present where they experienced their medical trauma.

Healthcare professionals

Trauma is also experienced by healthcare professionals. According to the 2021 census, in the U.S., there are approximately 9.8 million healthcare practitioners (physicians, surgeons, and RNs), 5.3 million nursing assistants (home health or personal aids), and an estimated 4.6 million first responders (EMTs, paramedics, firefighters), all of whom attempt to deliver the best care to their patients. Unfortunately, many have experienced negative patient outcomes, which has resulted in trauma. For instance, healthcare professionals may respond to an emergency in a way that results in a negative consequence to their patient or accidentally perform a medical error when treating a patient.

In the field examples: Trauma may be triggered when interviewing parents of children with chronic disease.

During two remote studies with parents and their children, several parents became emotional when discussing the challenges and fears they faced given their child’s illness or treatment. The researchers observed the parent become emotional and describe how devastating it was to watch their child experience life with their respective chronic disease. The presence of their child at the interview, the instructional materials, interview questions, medical devices being evaluated, or just the fact that the remote interviews were taking place at their homes (where the parents likely spend much of their time with their chronically ill child) all could serve as reminders for past trauma and trigger recall.

Throughout the sessions, the moderators listened empathetically and respectfully steered the conversation back to the interview. The goal was to ensure that the participants felt heard, while still gathering the required data to achieve a successful design that improves patient care. The bottom line is that a child’s diagnosis and treatment can be traumatic for both the child and their parents. While it’s important to get the data we need, we also must recognize that our participants are real people who have dealt with a potentially traumatic experience.

Recent traumatic events may be more likely to be recalled.

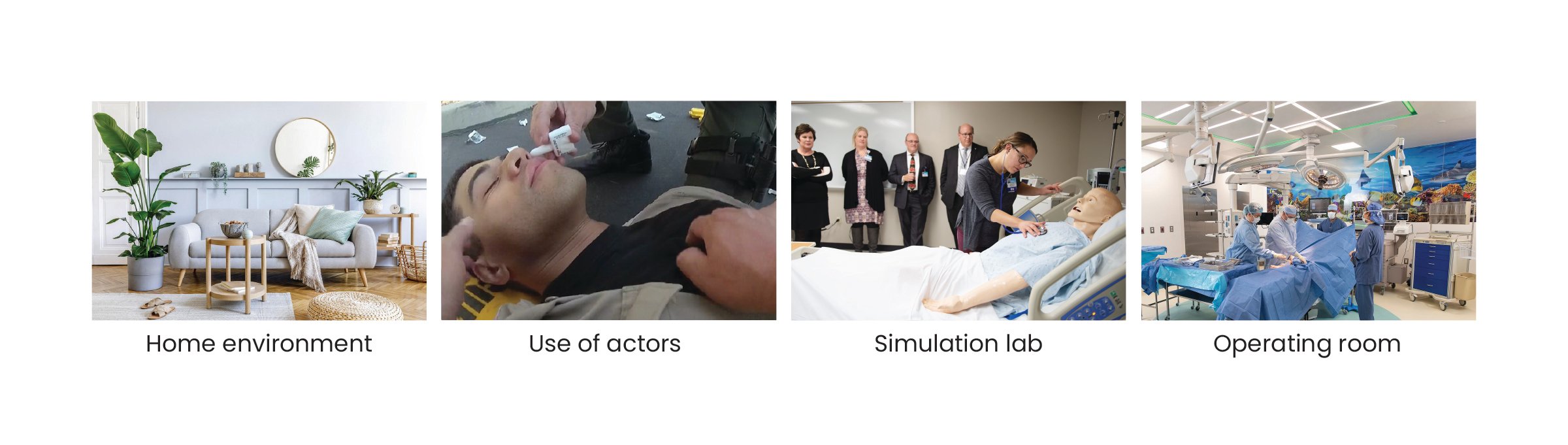

Participants who have experienced a recent trauma may be more vulnerable to recalling that trauma. We recruited caregivers of cancer patients to participate in a formative usability study of an injection device; the inclusion criteria required that the cancer diagnosis was within the last year. The simulated-use environment was staged as a living room with comfortable chairs and a coffee table, and a mannequin was used to simulate the patient. The caregivers were instructed to interact with and administer the injection to the mannequin just as they would to the person that they normally care for. The setting, the device, and the study materials all could serve as reminders of trauma.

We learned just before the session that a participant’s daughter had passed away two weeks before from cancer, but that they still wanted to participate. The moderator, in this case, was prepared to watch for signs of emotional distress. The participant was outgoing and communicative throughout the use scenarios, but openly wept by the end of the session. The moderator listened empathetically and asked if they would like to take a break or end the session early. The participant declined and stated that they wanted to finish the remainder of the session. The key take-away is that trauma may not always be immediately visible, and participants may express trauma at any point during the session.

Use of actors increases the realism, which may also increase the likelihood of trauma recall.

We sometimes include actors in a simulated-use environment to increase the realism of a use scenario, which may in turn increase the likelihood that a participant may recall trauma. One example is a study in which participants were evaluating the usability of a drug delivery device used for overdose intervention. The actor portrayed the role of the person who had overdosed, and the participants were instructed to simulate treatment to the actor. The use environment in this case was similar to that of an actual drug overdose, in that the actor “lost consciousness” during the session, simulating the emergent nature of the situation. Simulating an emergency in this case was important so that we could determine if users could safely and effectively use the device under this kind of pressure. Midway through the actor’s performance, one participant began to cry. The actor’s performance, the device, or the study materials all could serve as reminders of trauma to the participant.

The moderator paused the session and asked the participant if they would like to take a break. The participant expressed that they were uncomfortable with the scenario because they have family members who have experienced a drug overdose. The moderator decided to end the session to protect the participant from experiencing additional distress/trauma. The key takeaway in this example, is to know when it’s appropriate to end a session to protect the participant’s health.

Additional simulated-use environments.

Simulated labs or operating rooms might also trigger traumatic responses if a healthcare provider or first responder experienced past trauma due to a particularly difficult case, a past medical error, or recent loss of a patient.

Best Practices for HFEs

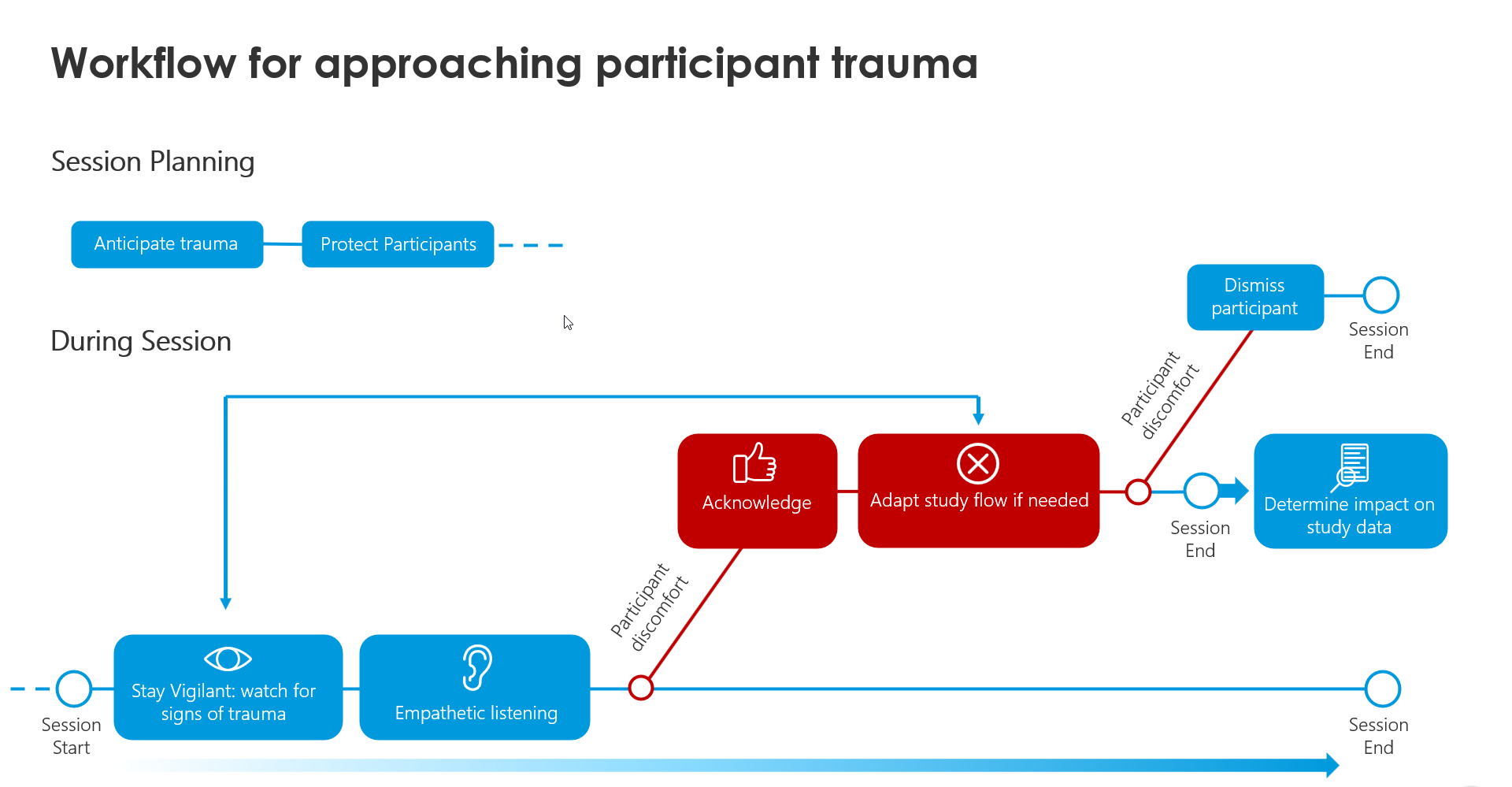

Human factors professionals can plan, facilitate, and analyze usability studies that may trigger traumatic responses in participants.

Session Planning: Anticipate participant trauma

Consider potential medical trauma events that the user group population may have experienced if they have prior experience with the device/system. For instance, if you’re researching a device related to dialysis and are recruiting dialysis patients as participants for a usability study, browse through the Manufacturer And User Facility Device Experience (MAUDE) or FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) databases to investigate known problems with the system. It’s worth identifying the common adverse events related to the device, so that you can be mindful about the stimuli that you include in the simulated-use environment and anticipate how participants may react when interacting with them. Remember that you’re reading about real people that have experienced those traumas, which may have changed their lives.

Session Planning: Inform and protect participants

Consider how sensory stimuli and secondhand reminders present in the simulated-use environment may trigger memory recollection in participants. The triggers will be present, so do what you can to protect the participant and help them mentally prepare prior to the session. A comprehensive description of the simulated-use environment in the Recruitment Screener and Informed Consent Form helps with this. The research staff should also carefully review the simulated use environment description in the Study Protocol and Institutional Review Board (IRB) submission to ensure that it fully captures what stimuli may be presented during the study sessions. Consider submitting the study protocol for IRB approval even if there aren’t physical safety concerns (e.g., needle stick injuries, real drug product) if you suspect that emotional trauma could be triggered based on the simulated use-environment. This way, all participants and study personnel are familiar with the simulated-use environment prior to the session.

During Session: Stay vigilant

Be aware that medical trauma is not always “visible”. Medical trauma expression can take many shapes and sizes and participants may recall the trauma at any point during the session. It’s especially important to stay vigilant as use-environment or device stimuli become more salient, as they may be more likely to trigger trauma recall. The moderator should keep this in mind when interviewing all participants, even those who may appear outgoing or unaffected.

During Session: Recognize signs of discomfort

When moderating, pay attention to the participant’s nonverbal cues of discomfort, especially in the presence of use-environment stimuli. These cues may indicate that the participant is recalling a traumatic event. Cues may include crying, avoiding eye contact or deflecting questions, as well as if they physically shift their body language, or change the tone in their voice or pace of their speech. If this happens, the moderator should affirm the participant and say “I understand that this may be a difficult conversation. Are you comfortable continuing on? Would you like to take a break?” The session should only continue if the participant agrees to continue.

During Session: Listen with empathy

Use empathetic listening throughout the session to uncover possible causes of trauma and if any environmental or device stimuli were specifically relevant to that trauma recall. If you hear the participant say something that may reference a traumatic event, let the participant know that you heard what they said and that you value that they shared that story with you.

During Session: Respectfully steer the discussion

Throughout the usability session, we often ask about participants’ pain points with the device, which can unintentionally lead to tangents related to early traumatic experiences. If this occurs, saying “Thank you for sharing that information with me. How might we design this system to prevent that from happening or help you avoid feeling that way?” can help. If a participant goes into greater detail about their trauma, it’s important to encourage them to feel that they are a part of the solution. The goal here is to create a space so that the participant is honest and open to exchanging ideas that may lead to meaningful product change.

During Session: Consider language used in root cause interview

When conducting the root cause analysis for a usability issue, use language that is understanding and accepting of all responses. Emphasize that there is no right or wrong answer and remind the participant that they are not being evaluated, rather, the system is. Do not use language that accuses the participant of doing something right or wrong, as this may increase their feeling of vulnerability. A common response you might hear is “I forgot”. Instead of following up with “Why did you forget?”, consider saying “Is there anything about the design of the system that may have made it easy to forget?” The root cause interview is helpful only if the participant is comfortable and willing to reflect on how and why they performed the actions that they did. It’s important for the participant to reflect honestly and thoughtfully about if a certain device or environmental stimulus had caused him to experience distress and whether that distress impacted his decisions.

During Session: Adapt the study flow

If a participant expresses discomfort or signs of trauma recall, the moderator should check in with the participant to confirm that they are comfortable continuing with the session. Adapt the study session flow if necessary to avoid the remaining tasks or questions that may result in additional participant distress. If the participant refers to a specific stimulus in the simulated use-environment that may have triggered their distress, consider reducing the saliency of that stimulus removing that it entirely. It’s up to the moderator and onsite study team to use their best judgement in determining when it’s unsafe for the participant and to respectfully dismiss the participant.

Study Analysis: Impact to data

If a participant experiences a traumatic response, it might be tempting to write off that participant as an outlier and not include their data in the study report. However, this is the opposite of what you should do! Instead, engage in root cause analysis to determine the effect of the distress on participant performance. Did the distressed participant’s data differ from those for whom you didn’t observe distress? Asking these questions may provide key insights about the device or intended use- environment that you had not previously considered. What was the stimulus that caused the participant’s distress? What was their response? Provide a summary of the event in your study report and indicate any adaptations to the study session in the Deviations Section.

It’s important to ask yourself: Is the distress that the participant experienced in the usability study representative of the distress they could experience when using the device in real life? If so, make sure to document the following:

- Ensure that the study report fully documents all use errors, close calls, and difficulties related to the participant’s distress.

- Design the device interface so that it anticipates user distress and simplifies use so that it does not add to the user’s level of distress (e.g., minimize cognitive load, include affordances for how to use the device, provide support in user documentation and/or training).

- Update the uFMEA if the emotional distress leads to a new hazard that had not already been accounted for in risk documentation.

- Update the Use Specification document to include emotional distress as a possible use case.

Conclusion:

It’s our responsibility as researchers to protect usability study participants from physical and emotional harm as best as we can and manage distress due to past trauma. The data we uncover is instrumental in the product development process and ensures devices that are safe and effective for use, and a better patient experience.

Image References:

Collage 1:

- “What should you eat in Ramadan if you are diabetic.” Times of India. 09 May 2019. https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/life-style/food-news/what-should-you-eat-in-ramadan-if-you-are-diabetic/articleshow/69233128.cms

- Kolata, Gina. “Lessons of heart disease, learned and ignored.” New York Times. 08 April 2007. https://www.nytimes.com/2007/04/08/health/08heart.html

- “Improving patient experiences in cancer clinical trials.” Penn Today, 13 August 2021. https://penntoday.upenn.edu/news/improving-patient-experiences-cancer-clinical-trials

- “Anxiety.” Medicine Plus. n.d. https://medlineplus.gov/anxiety.htmlC

Collage 2:

- "Clinical negligence FAQs” Williamsons-Solicitors. n.d. https://www.williamsons-solicitors.co.uk/services/clinical-negligence/faqs/

- “Lifetime physical activity not linked to risk for ALS.” Health Day. 21 October 2021. https://consumer.healthday.com/risk-of-als-not-linked-to-physical-activity-five-to-55-years-earlier-2655311000.html

- “Responding to emergencies in the workplace.” Safety Line. n.d. https://safetylineloneworker.com/blog/responding-to-emergencies-in-the-workplace

Collage 3:

- Molvar, Kari. “12 Home decor ideas to refresh your home without renovating.” Forbes. 02 September 2021. https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbes-personal-shopper/2021/09/02/best-home-decor-ideas/?sh=193f43778f36

- Goforth, Claire. “San Digeo county sheriff. ”Dailydot, 06 August 2021. https://www.dailydot.com/debug/san-diego-sheriffs-department-fake-fentanyl-overdose-video/. 3. “Penn State Health St. Joseph unveils new nursing simulation lab.

- ”Penn State University. 12 December 2019. https://www.psu.edu/news/academics/story/penn-state-health-st-joseph-unveils-new-nursing-simulation-lab/

- Molinet, Jason. “Cohen Children’s Medical Center unveils $110M pediatric surgical operating complex.” Northwell Health. 09 August 2022. https://www.northwell.edu/news/the-latest/cohen-children-s-medical-center-unveils-110m-pediatric-surgical-operating-complex